Mutually Destructive “Reciprocal Tariffs”

The second quarter of this year began with Trump shaking the financial markets with his globally enforced reciprocal tariffs. Although he announced a three-month delay after just one day—giving other countries time to reach agreements with the US—by the end of June, only a few had finalised deals.

Apart from China, which faced the highest tariff increases, only the UK had successfully signed an agreement. Others, including India, Japan, Canada, and the EU, remained in negotiation.

With the tariff delay deadline of 9 July rapidly approaching, the main focus for early Q3 will be on how talks progress. Most major trading partners are now deep in negotiation, and even if no formal agreement is reached by the deadline, it’s unlikely that Trump would abruptly reinstate the tariffs.

There is a high probability of further extensions, meaning markets need not worry about another global crash like that of April.

Looking back, these reciprocal tariffs caused a significant rise in US imports during Q1, as companies scrambled to stockpile goods ahead of anticipated price increases. This surge led to a negative annualised GDP growth of -0.2% for the quarter.

Over a longer timeline, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania forecasts that the tariff policy could generate over $5.2 trillion in federal revenue over the next decade. However, slower economic growth and declining productivity could reduce this figure, potentially worsening the federal deficit.

While some sectors may see temporary reshoring of manufacturing, the policy has yet to prove any real long-term benefit to the overall US economy.

Trump Himself Is the Main Reason the Fed Hesitates

The uncertainty brought on by the reciprocal tariffs has placed more pressure on businesses than the tariffs themselves. No one knows what Trump will do next. His unpredictability has led companies to adopt a conservative outlook on earnings, discouraging investors and creating a need for positive news to stimulate markets.

Whenever US economic data shows signs supporting rate cuts—be it falling inflation or a tightening labour market—Trump immediately calls on Fed Chair Jerome Powell to lower rates.

He aims to boost market confidence through monetary easing and has repeatedly criticised the Fed’s slow response. Trump even gave Powell the nickname “Mr. Too Late”.

Despite months of pressure, Q2’s rate decisions and Fed officials’ speeches suggest the efforts have had little impact—or even the opposite effect. The Fed held rates steady in both Q2 meetings at 4.25–4.5%, the same level since the December 2024 cut.

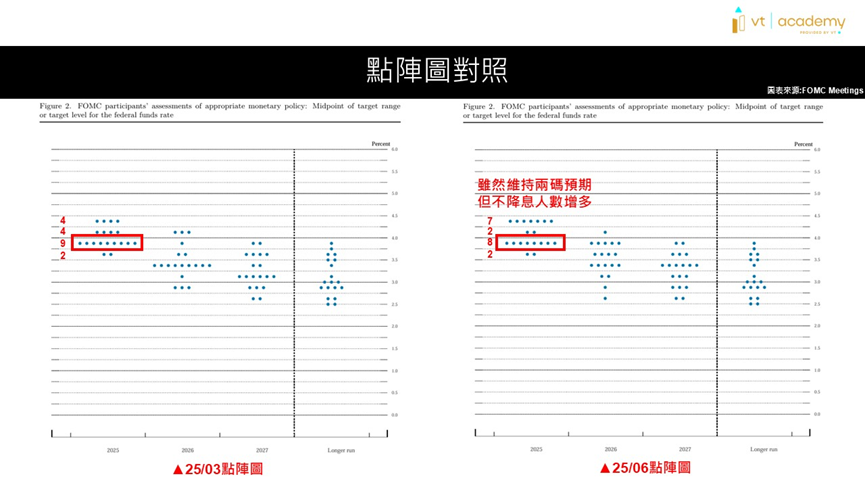

OMC dot chart in March 25 VS. June 25

The June dot plot shows that the majority of members still expect two cuts in 2025, aiming for 3.75–4.0%. But the distribution has shifted: the number of officials opposing any rate cuts rose from 4 to 7, while those supporting two cuts dropped from 9 to 8.

Just one more hawkish shift could reduce the expected rate cuts this year from two to one. The 2026 forecast was also revised upwards to 3.5–3.75%, cutting the expected reduction from two to one rate cut.

This shows that the Fed is becoming more cautious about easing. Futures markets now expect 25bps cuts in both September and December. However, if inflation rebounds or the labour market strengthens, even those could be postponed.

Powell’s remarks suggest this caution is driven largely by risks stemming from Trump’s policy decisions. Ironically, doing less might help the Fed act sooner.

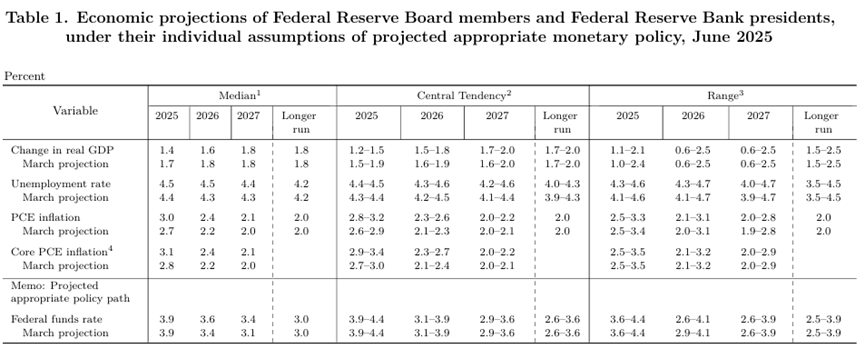

Fed’s Latest Forecasts Signal Downgrades in Growth

In the most recent FOMC economic projections, the Fed cut its Q2 GDP forecast from 1.7% to 1.4%. It raised its unemployment forecast from 4.4% to 4.5%, and both headline and core inflation projections from 2.7% to 3.0%, and from 2.8% to 3.1%, respectively. This reflects growing concern about economic uncertainty (see Fig. 2).

In the June statement, the Fed again highlighted the volatility in net exports, while removing references to heightened unemployment and inflation risks—suggesting recent data has stabilised slightly. The economic outlook was revised from “continued improvement” in May to “moderation at high levels”.

The forward guidance remains unchanged: the Fed still sees potential for further rate cuts, but will evaluate the timing and scale with increased caution.

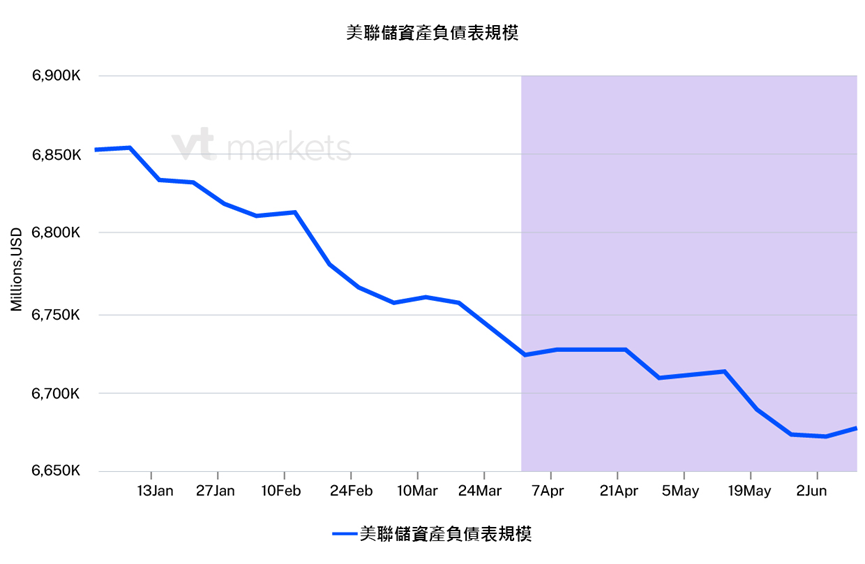

Elsewhere, the Fed’s balance sheet reduction has slowed. The pace of asset runoff decreased from $50–55 billion to around $36 billion per month.

Since early April, the balance sheet has shrunk from $7.23 trillion to $6.68 trillion, a new recent low (see Fig. 3).

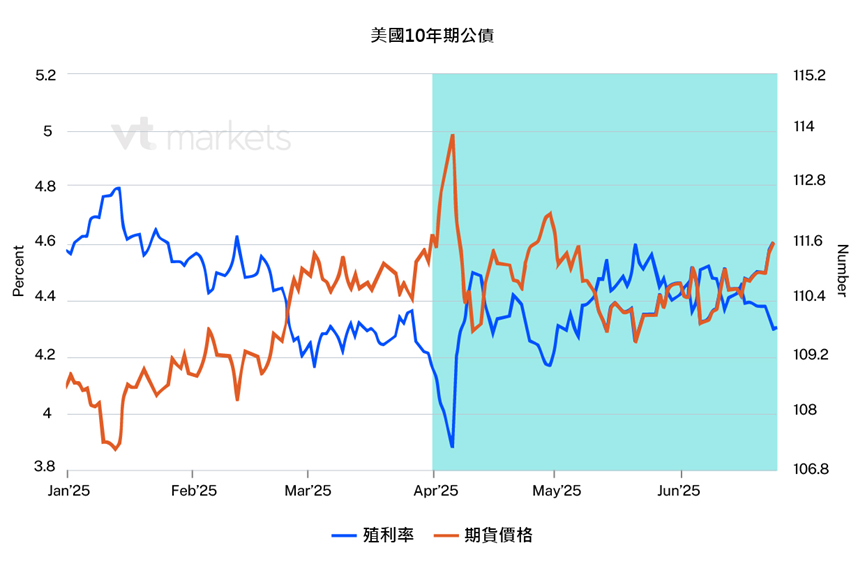

Looking to Q3, Trump’s “Big and Beautiful” fiscal bill has passed the House and may clear the Senate by 4 July. While 10-year Treasury yields have recently fallen due to rate cut expectations (see Fig. 4), the bill would require the Treasury to increase debt issuance.

A rise in government bonds could lower prices and push yields higher, raising borrowing costs and adding to fiscal pressure. Markets will closely watch the size of these issuances and whether the TGA (Treasury General Account) target at quarter-end needs sharp replenishment.

Global Easing Continues—but the Dollar Doesn’t Benefit

While the Fed holds its ground, central banks elsewhere have pressed ahead with easing. The ECB has cut rates eight times since June 2024—including a double cut in September.

Even though inflation in the eurozone has now dropped to 1.9%, in line with the ECB’s target, President Christine Lagarde noted that economic risks still skew to the downside. Given lingering global trade uncertainty, the ECB is expected to continue easing, though at a slower pace.

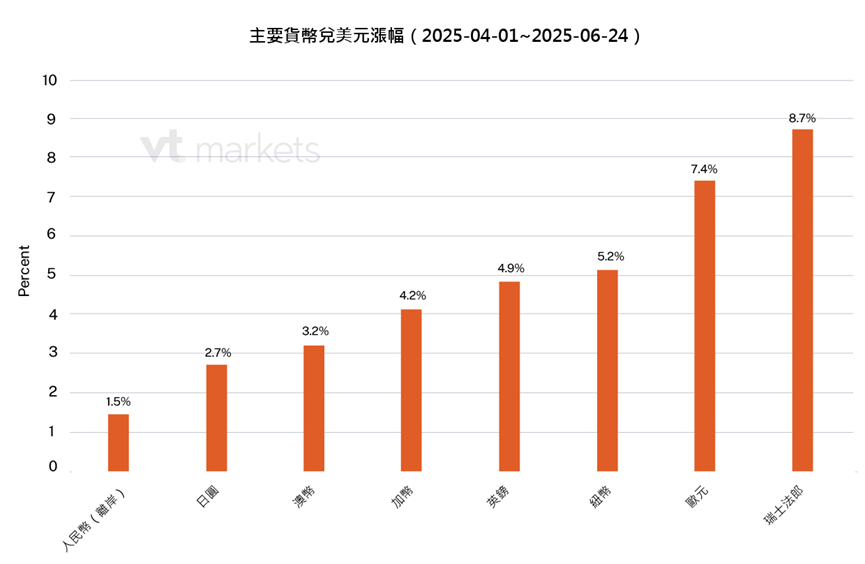

Other central banks—including the UK, Canada, Norway, and Sweden—have also cut rates this year. However, the US dollar has continued to show weakness in Q2, mirroring Q1’s performance (see Fig. 5). It has failed to strengthen against other currencies despite widening rate differentials.

This suggests that the uncertainty surrounding US fiscal deficits and tariff policy is eroding the dollar’s appeal.

All three major credit rating agencies have downgraded US sovereign credit ratings. If the fiscal bill passes, the debt ceiling will climb to $40 trillion, increasing fears about long-term solvency. This could further weigh on the dollar’s outlook.

From a technical perspective, the dollar index hasn’t rebounded in Q2; instead, it has dropped back to levels last seen in early 2022 (see Fig. 6). If the Fed cuts rates in Q3 as expected, this weakening trend may be even harder to reverse.